Aimee Labourne: VACMA project at Gaada

We recently had the pleasure of supporting Shetland artist, Aimee Labourne, with a project supported by Creative Scotland’s Visual Art and Craft Maker Award (VACMA).

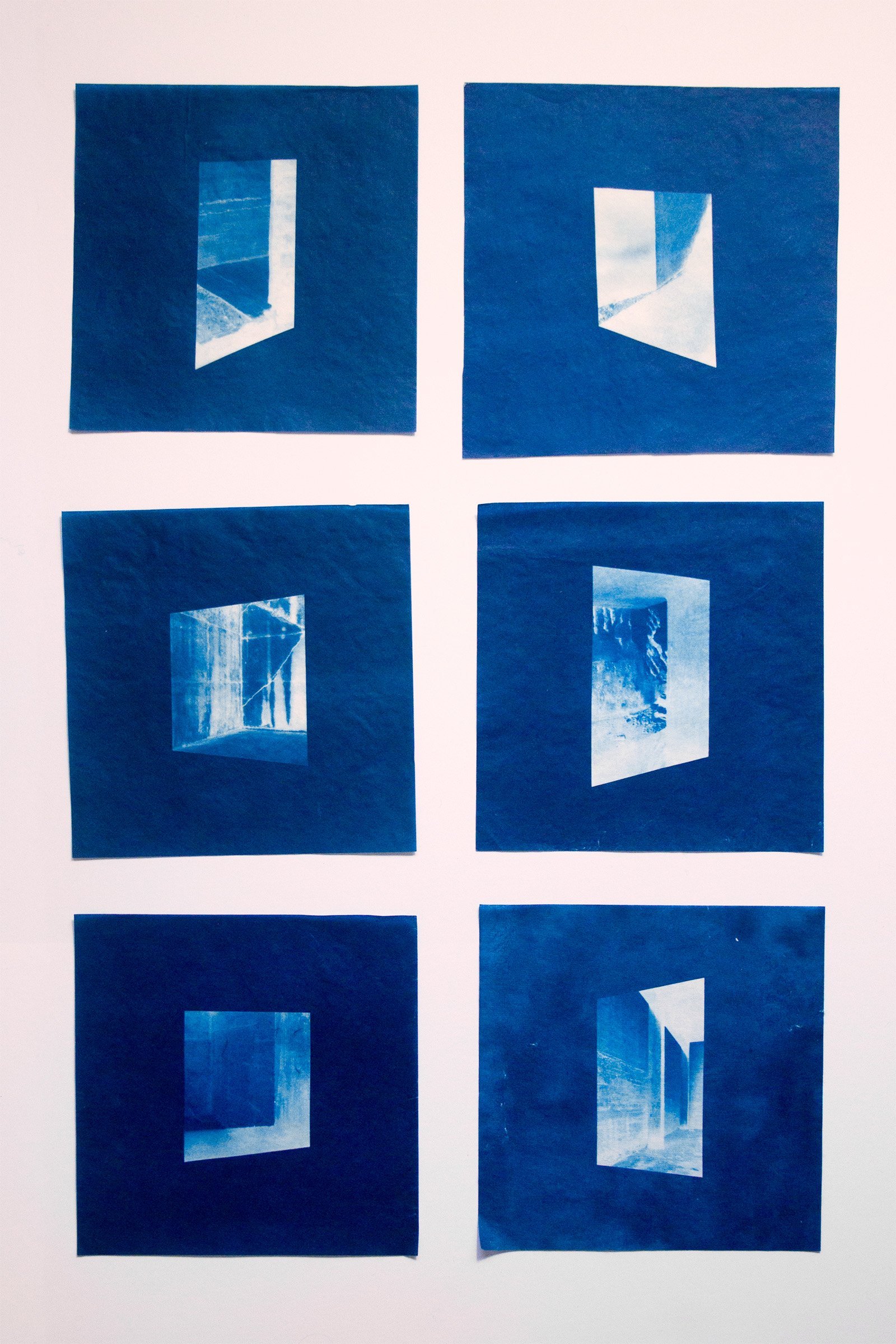

Aimee used Gaada’s facilities and tutor time to realise some incredible cyanotype work. She generously shared an insight into her project, below:

“Drawn to the islands’ rich heritage and the fascinating landscapes to be found here, I moved to Shetland in 2016. Since then, my work has become increasingly focused on our understanding of landscape and nature, and I’m particularly interested in how changes such as environmental destruction, modern ‘progress’ and shifting contemporary ideologies are affecting this.

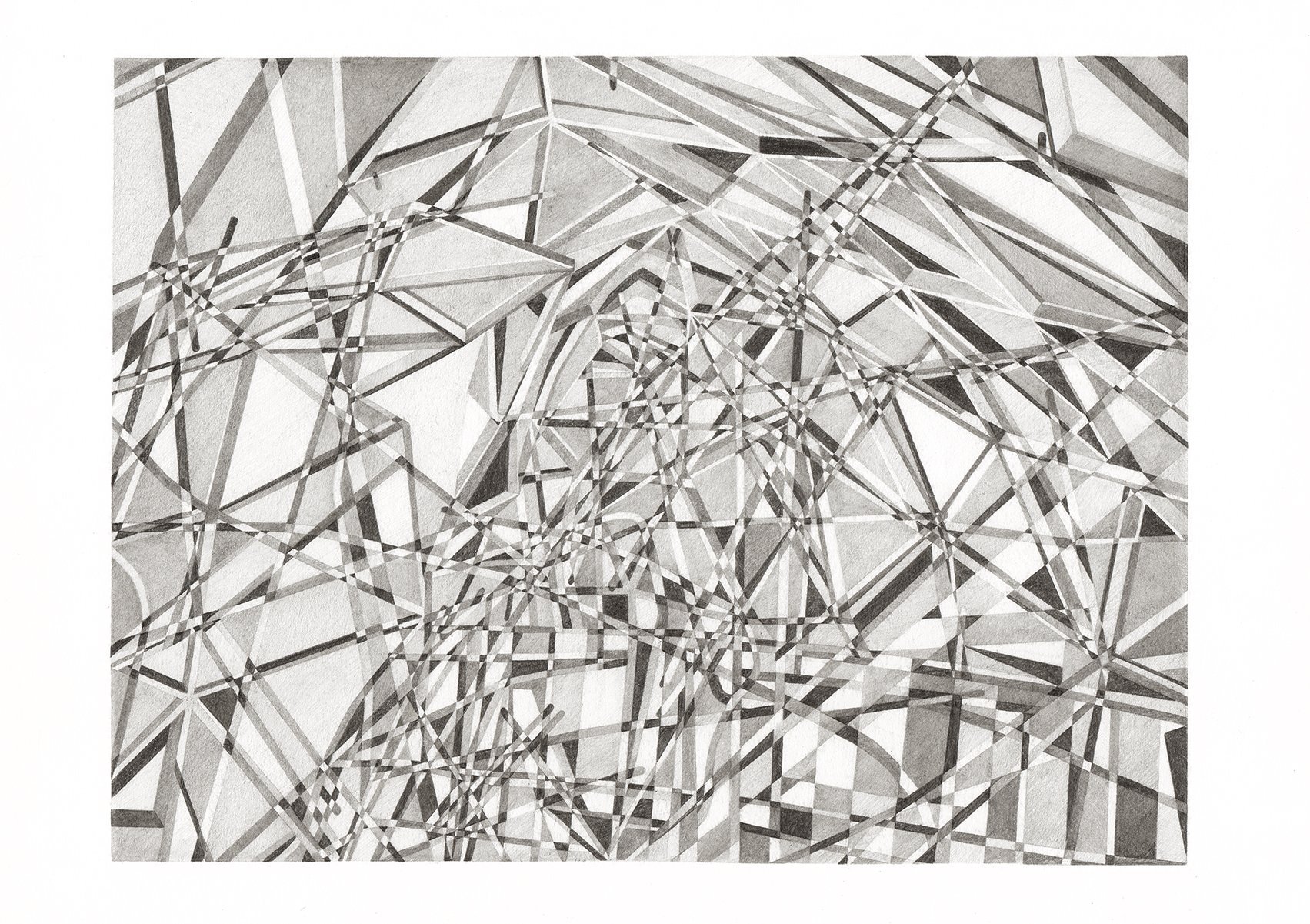

My practice focuses on drawing, and I tend to work representationally using traditional media such as pencil and charcoal to investigate form through line. However, photography also shapes my work, so dominant in today’s world of rapid image consumption. I am interested in the many ways both media can inform each other and in different kinds of pictorial space, which can convey different notions of time and ideology.

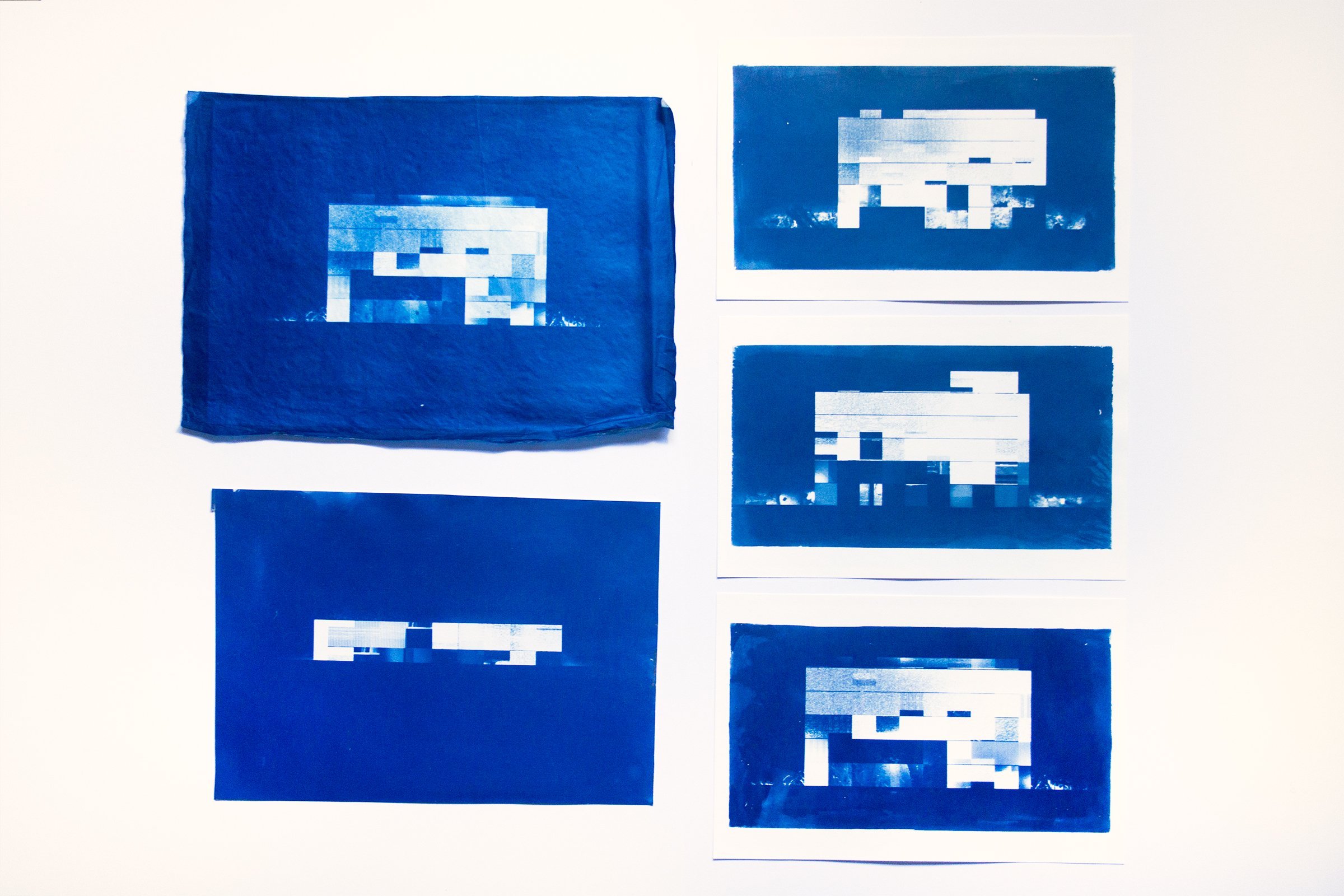

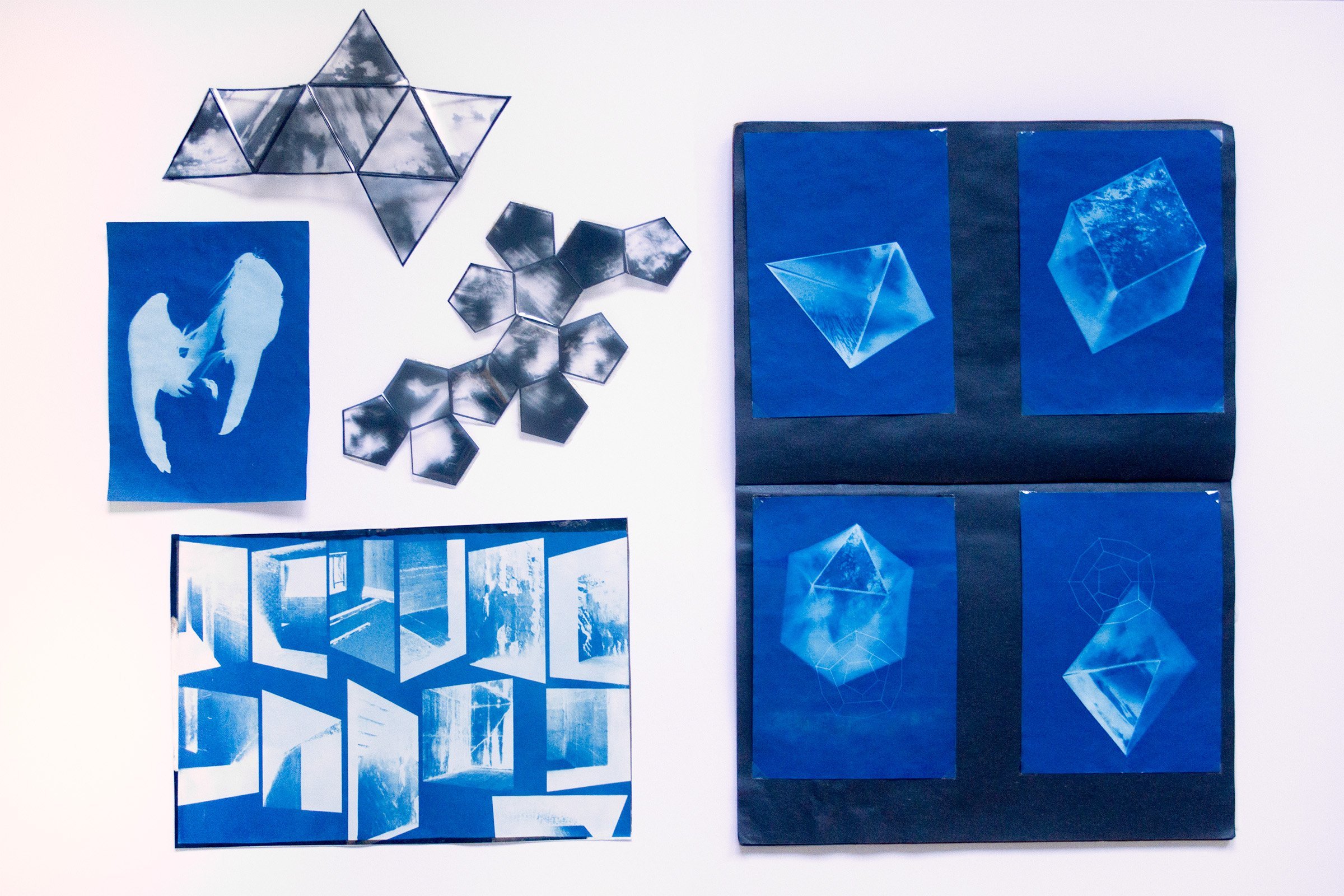

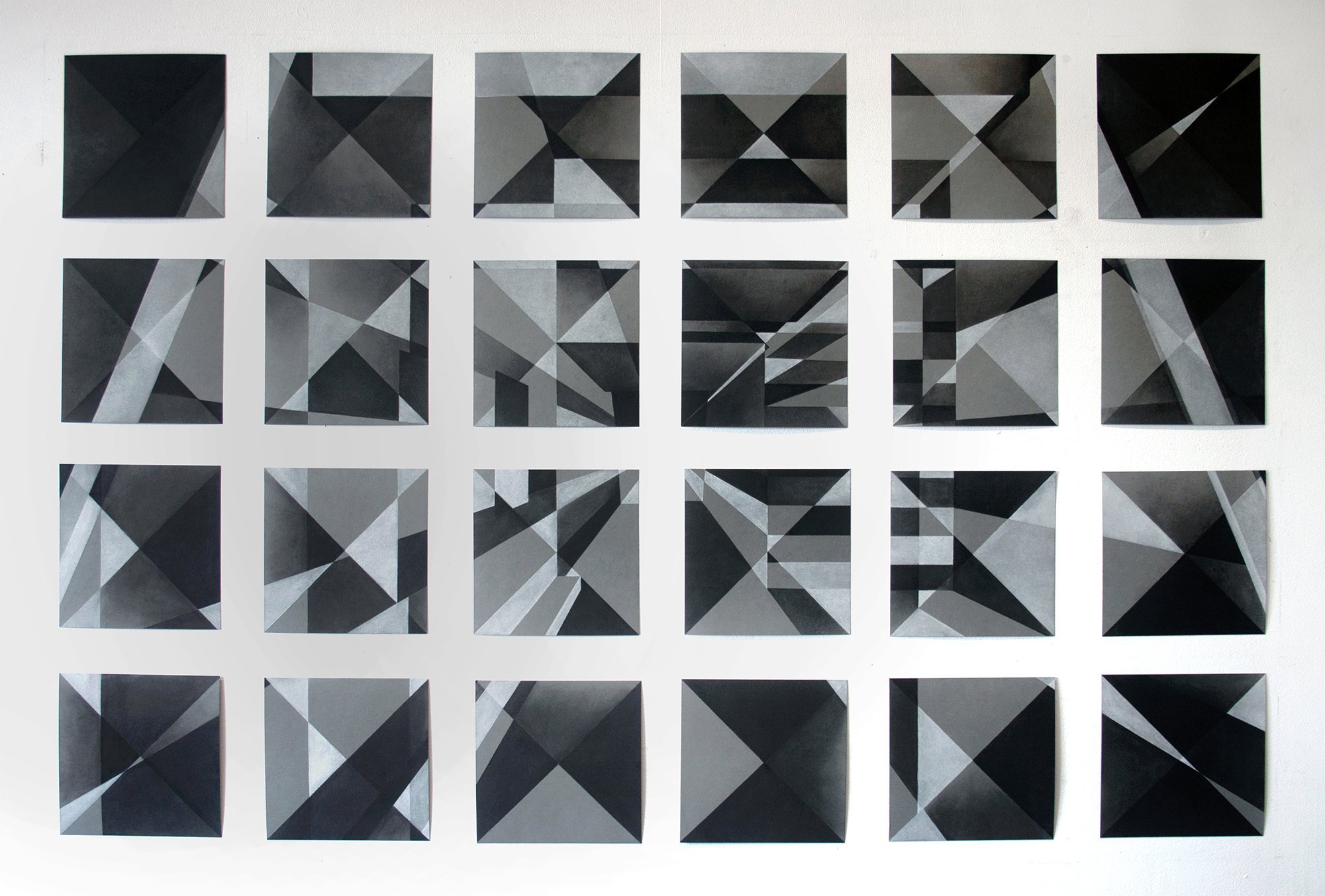

My VACMA in 2021, supported by time at Gaada, was a creative development project leading on from ideas begun during lockdown. Since 2015, I’ve been fascinated by the many WWII ruin-sites scattered across Shetland - eerie spaces, decaying yet futuristic and strangely evocative of Modernist buildings. In spring/summer 2020 whilst everything was in chaos, I had spent long days making small scale drawings that explored shifting sense of time and space, inspired by past experiences of visiting Shetland’s war ruins. In these works, I was experimenting with ways of fragmenting their brutally functional architecture and ways of disrupting and abstracting the perspectival constructed space we usually find in images of buildings. I very much liked the idea of suggesting not only physical decay, but also the decay of pictorial depth and stability in the image. Later lockdown work was still small but I started to think about ways drawings could work together to become larger arrangements across the wall, occupying more space and exploring a fragmenting, dissolving picture surface. During lockdown, I also had the time to try cyanotype printing again. I had previously experimented with this early photographic technique (using printed negatives or objects and prepared paper exposed to sunlight or UV) but was again fascinated by how cyanotype included nature and time in its slow process, which seemed very pertinent during 2020. As with the drawings, I explored uncertain architectural spaces, and became particularly interested in positive/negative relationships – how introducing unexpected inversions can dramatically change how we read space, and so create disorientation.

Time at Gaada was a brilliant opportunity to progress with this work. Looking back, the drawings and cyanotypes I made during lockdown were quite obsessive – during those months, their small scale and the time-consuming processes involved were how I had felt like working. By consuming my focus and energy, they had felt freeing – impossible places I could construct and move around in. But as the year went along, I felt an interest in opening work up too. I wished to increase the scale of work, explore translucency, and use projection to plan more complex works on new surfaces. I also wished to research more ways of using drawing, photography, and cyanotype together to make images.

At Gaada, I explored images of war-ruins that evoked architectural drawings and elevations - I was interested in the paradox of making a visual reference to projected futures (cyanotypes or ‘blue-prints’ being synonymous with architect’s plans) for these explorations of ruins. Starting with my lockdown work, we explored some ideas with different equipment including a scanner, Illustrator software and a plotter to produce vector graphic drawings. This interestingly led to more ideas about how interactions between drawing and technology could explore conceptual space and surface, and input/output (i.e. where processes of manipulation, disruption, distortion, chance and ‘decay’ could be inserted). This importantly led to a more process-based outlook for my next ideas. I went away from my first day at Gaada with lots of thoughts about how images that looked chaotic could be created by a ‘logical’ machine, and more inspired to use technology in my drawing. We had also importantly explored the process of cyanotype by mixing chemical recipes, honing ways of coating paper and trying different papers. The lightbox at Gaada was crucial in giving a fixed aspect to the cyanotype process. At home using just the sun, there had always been too many variables for my experiments to be very scientific, but this equipment meant I could really start to analyse aspects I wanted to explore in the work, such as contrast and depth of blue.

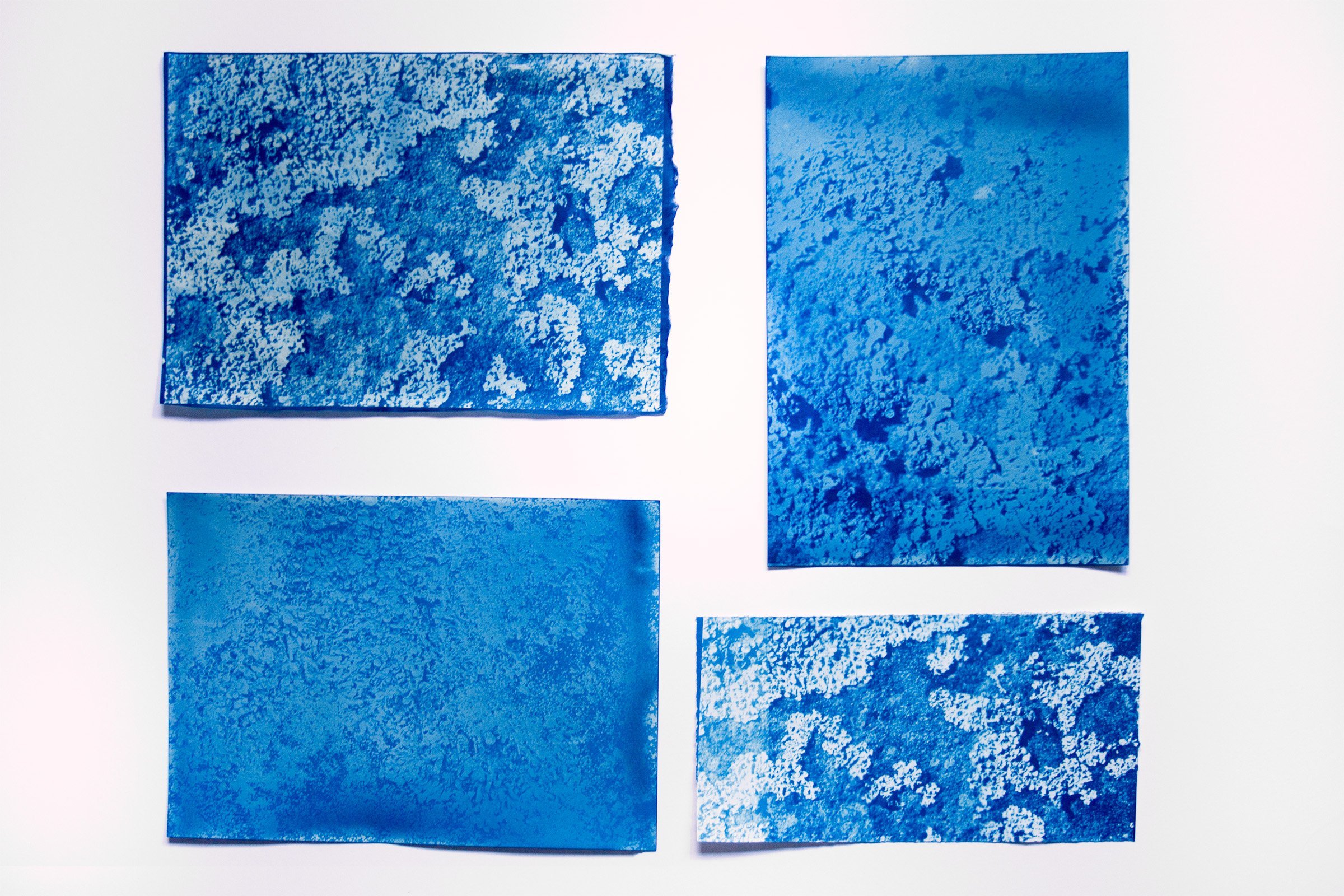

Later in 2021, I was delighted to be part of a group exhibition called ‘Hidden Flowers Bloom Most Beautifully’ which showed at Mareel and brought together artists from Shetland and Switzerland. Exploring themes of contemporary art in rural places, nature’s destruction and how we conceive of our place in nature, my work for this project focused on lichen. I was now more sensitive to technicalities in the cyanotype process and refined things until I could produce a print which reflected what I wished to communicate about surface and scale for my lichen image. As a direct result of my VACMA time at Gaada, I was able to produce a cyanotype limited edition for the accompanying publication for this show, expanding the reach of my work and scope of my ideas.

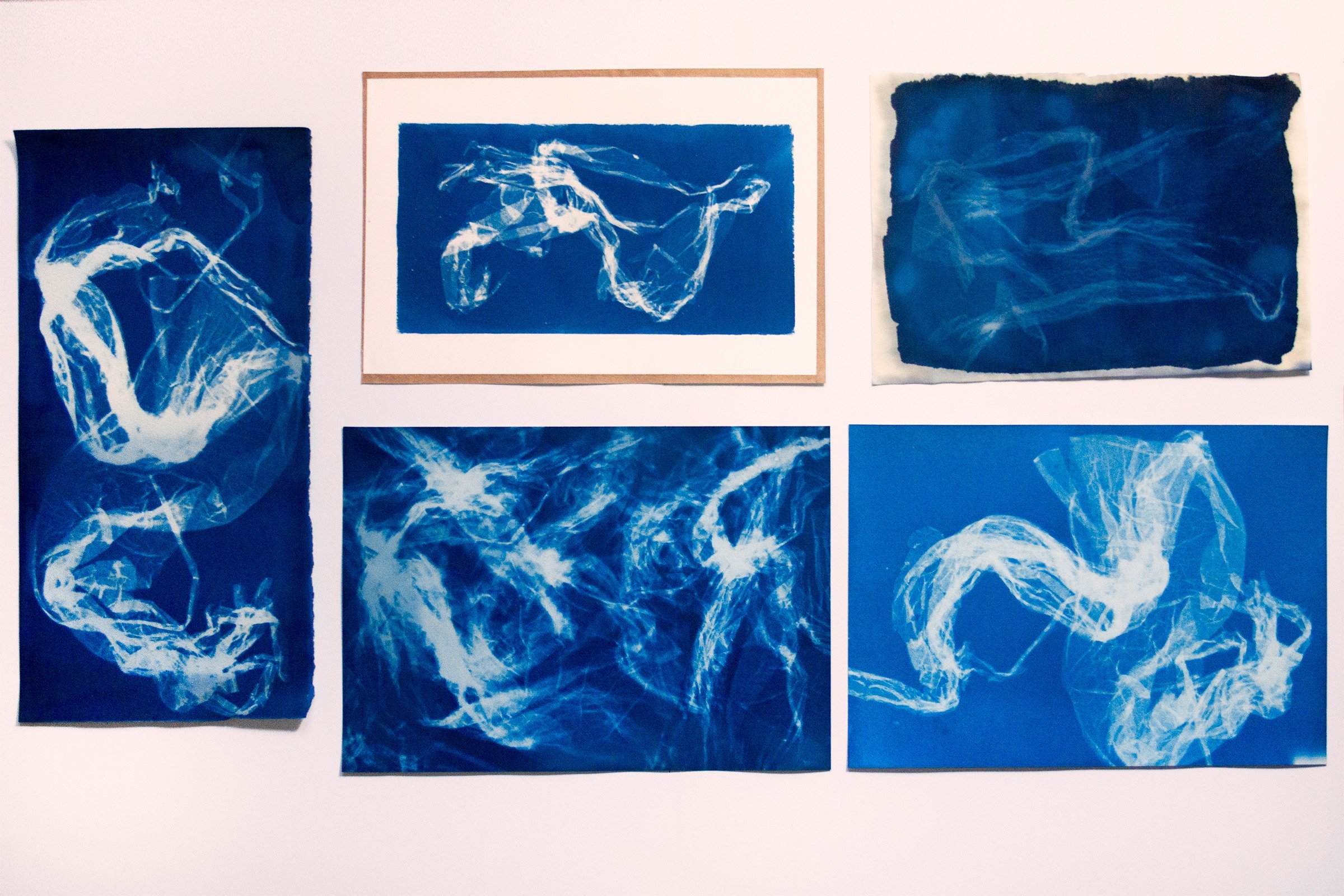

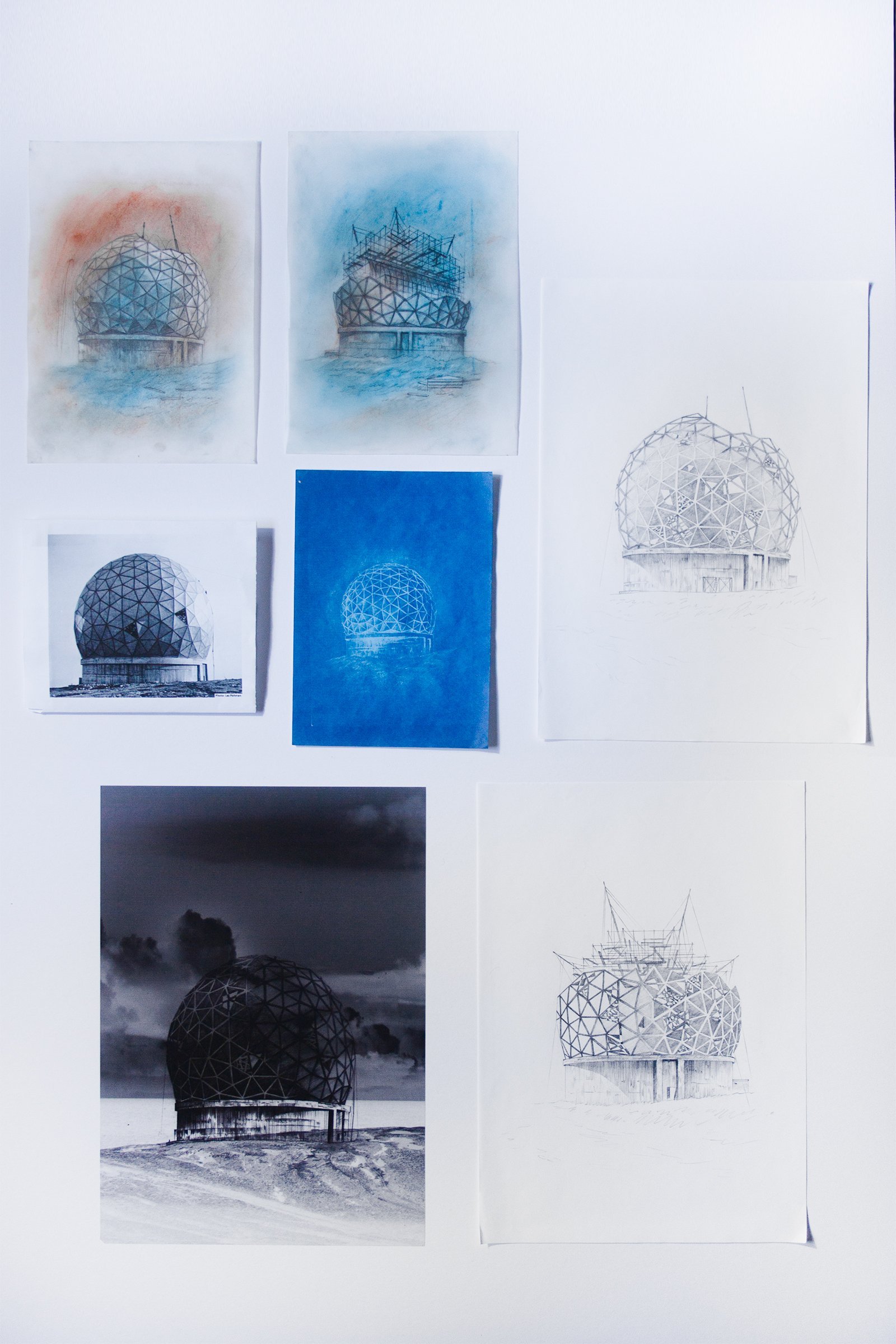

I’ve continued to be fascinated with ruins, space and ways of opening-up images using drawing, photography, cyanotype, and digital editing. For example, an idea of drawing radomes has evolved several times. In 2015, I used historical images from Cold-War era Saxa Vord to make pencil and chalk drawings. Feeling they needed to evolve, I had made cyanotypes from these drawings, but I now realised I wished to continue with a photographic quality too. Whilst making new pencil drawings (to scan-in and digitally layer with photographs to produce cyanotype acetates) I then became fascinated with the inversions happening when shading the geodesic structure. I now wish to explore shading complex structure-surfaces further to take my drawings and prints in more abstract directions. This dialogue between photography, print and drawing begun at Gaada has, I feel, broadened the processes involved in my work and expanded my notions of what is representational and what is ‘abstract’. More recently, I’ve continued to use cyanotype to consider other themes of humans and our place in nature. This year, I hope to develop more prints made from fragments of plastic collected from the environment, referencing the historical use of cyanotype in scientific study. In these, pieces of plastic look almost organic - their fragile stillness like preserved botanical specimens belies the fact that plastics in the environment will persist for hundreds of years, our actions having innumerable consequences in nature.

Time spent at Gaada has had a huge effect on my practice and my approach to making work, and not only through my VACMA project but also through the wonderful Peer Group. It’s inspiring and supportive to have experienced the expertise, patience, and vision of folk at Gaada, and lovely to feel part of the network of artists across Shetland which has been drawn together.”

-

If you are based in Shetland and have an established arts or craft practice, like Aimee, you could be eligible to apply for Creative Scotland’s Visual Artist & Craft Maker Award (VACMA) or Open Project Funding. These funds are currently some of the best routes for artists to access specialist facilities + support from Gaada. Get in touch to tell us about your project!